War Stories by Lyle Hansen.

Section 6

Copyright† 2002

Surrender signing and on.

††††

†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

†††††††††††††

†††††††††††††

††††††††††

††††††††††

††††††††††††††††††††††

.

††††††††††††††††††††††

.

†††††††††††††††††††††††††

†††††††††††††††††††††††††

††††††

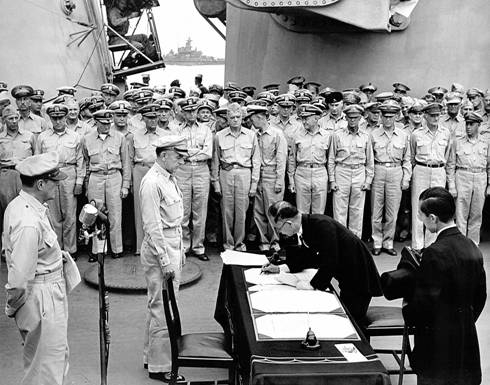

†The

Japanese delegationís arrival on the USS Missouri for the signing of the

surrender documents.

September 2, 1945.

Shigemetsu

signs for Emperor Hirohito.

Admiral Nimitz signs for the US

with† Gen. MacArtur, Adm. Halsey and Rear

Admiral Sherman looking on.††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† Gen. MacArthur signs as the new military governor

of† Japan while General Wainwright

and† British General Sir Arthur Percival

look on.† Wainwright and Percival had

just been released from a Japanese prisoner of war camp in Manchuria.

The city of Yokohama and Tokyo had been major targets of the bombing raids. The

wooden structures that had housed people and small factories for manufacture of

war materials were mostly reduced to ashes.†

In Yokohama, the US Consulate, the Post Office and the Frank Lloyd

Wright designed Grand Hotel were among buildings still nearly intact.† Windows had been blown out of most of the

buildings still standing.

††††††

††††††

†††††††††††

††††††††††††† Yokohama fire-bombing damage.† The shacks were put up from salvaged tin roof materials

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

Streetcars still operated.

††††††††††††††††††††† But some, like the one shown below, had burned† in the air raids,

†††††††††††

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

Yokosuka revisited.†††††††

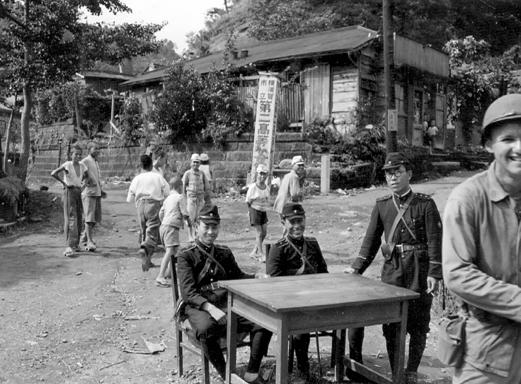

The attitude of the people during the first day or two was that of suspicion and fear.† I felt they believed we might barbecue them and have them for breakfast!† When that didnít happen, they became curious and more friendly. In the little village of Yokosuka where my friend Baker and I had such uneasy feelings on that first day, the differences were dramatic.† There were smiles, and no one ran off at our approach.†

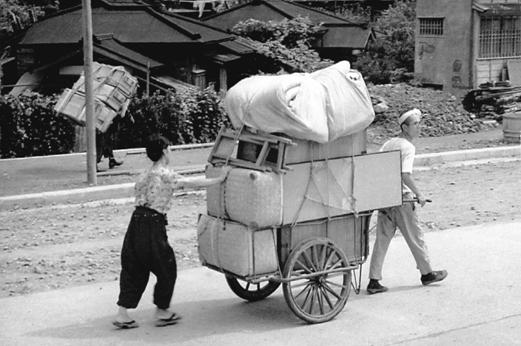

In Yokohama people began to come back to repair and rebuild.† Men still in uniform (almost every male was in uniform.) were helping their wives move pushcarts loaded with belongings. Some, lacking carts, moved huge loads on their backs.†† I felt the people here had a sense of hope for the future, they went right to work to rebuild.†

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† Returning

to Yokohama by the best means available.

†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

To face a new beginning?

How wonderful it would have been if I could have conversed with this man.† Was he just resting during a lunch break?† Was he disillusioned about the whole war experience?† Maybe he was sad thinking of relatives or friends lost, I can never know.† He knew no English, and after only about a week in the country, I had gathered very few Japanese words.† Fortunately, many Japanese had more knowledge of English than we did of their language.† Their pronunciation was odd, but understanding was possible.† It was culture shock for both them and us.

†††

†††

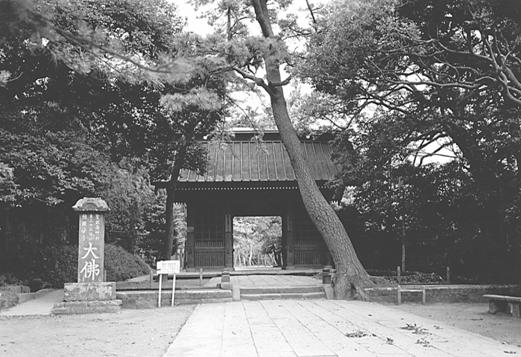

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† A shrine

entrance.† Mr. Rogers is looking it over

in the background.

††††††††† Some of the graceful architecture and beautiful gardens in the countryside were fascinating, and in stark contrast to the devastated city.

Inland and a few miles to the south of Yokosuka is Kamakura.† Here is the great bronze Buddha, said to be the largest in the world.

Entrance to the Great Buddha shrine at Kamakura

††††††††††††††††††††††††††

††††††††††††††††††††††††††

†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

The great Buddha at Kamakura.

Looking up at the inside of Buddhaís† head.

††††††††††††††††

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

Another roadside shrine.

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

Tokyo Rose was located and interviewed by a navy

camera† crew.

This interview with Tokyo

Rose took place a few days after US forces came ashore, before

our government decided to put her in prison and try her for treason.† Having been born in the U.S., she was a

U.S. citizen.† These photos were

given to me by one of the men in the crew shown in the upper photo.† I did not see her myself.

My time in Japan was short, only about ten days.† I left ahead of the rest of my unit because I began to have an upset stomach. Whether it was the excitement of having the war end and finally landing in Japan, or whether it was due to the K-rations for days on end, I donít know. Mr. Rogers decided that whatever it was, I should go back to Guam.† The rest of our unit followed a few days later.† I loaded my equipment and personal effects into a large seaplane, (PBM) and settled down for the ten-hour flight to Tinian.† The long taxi run in Tokyo Bay to get up flying speed seemed to last forever. From my position toward the rear of the plane, the engine noise was deafening. We were given cotton to stuff in our ears, but it wasnít very effective. To this day I blame some of my hearing loss on that flight. I was able to put my head into the pilotís cab for a few moments and found that up there, ahead of the engines, one could converse in near normal tones. We passengers could see some of the small volcanic islands in the chain that stretches to the south from Japan, but couldnít be sure which ones they were.

After landing at Tinian, the big seaplane was hauled up a ramp at the seaplane base.† A short time later I boarded a C-46 (Curtis Commando) for the flight on to Guam.† My normal hearing didnít come back for about three days.

Getting back to Cincpac was wonderful.† I found the mosquito-netted cot in a Quonset hut to be quite comfortable, and there were no fleas! And while the food was far from gourmet, it was a great improvement over the diet we existed on while in Japan.† My stomachaches disappeared after a few days.†

†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† Quonset Huts at Cincpac Headquarters on a night in

September, 1945.

I had several short photo assignments during this time at Guam. One was to

photograph the battleship Idaho being repaired in a floating drydock down at Apra Harbor.† To get out to it and to get a good view I needed a boat.† To my surprise, when I asked for one, I was assigned the admiralís barge and was taken around the harbor in great style!

†††††††† Another assignment was to cover the unloading of a merchant marine ship that had arrived with a load of livestock and seeds.† The U.S. Dept. of Agriculture had sent this in an attempt to get agriculture started again on the island. There were purebred dairy cattle, hogs, and sheep to be taken ashore.† They looked very out of place in this tropical setting to me.† I was told that the Japanese troops had slaughtered most of the livestock on Guam during their occupation. The Chamoro people had been used to water buffalo before, so I wondered how they would handle Holstein dairy cattle.† During the unloading of this ship, I was invited to eat the noon meal with the mechant crew.† They took me into their mess deck, where china plates were set on the table.† The cook was hard at work in his galley, which was at one end of the space.† He was grilling steaks, there were vegetables and real gravy for the potatoes.† I think there were about a dozen crewmen sitting down for the meal, and they were all complaining about the food.† Someone remarked that the cook deserved to be thrown over the side!† He was nervously watching to make sure the steaks were just right. After I had eaten the one he served me he wanted to know if it was all right, and was busy giving seconds to those who wanted more.† Not accustomed to such fare, I couldnít handle quantities of such wonderful food. Then, when I thought the meal was over, the cook came around with apple pie ala mode!† I knew then that in the next war I would try for the merchant marine.

†††††† One Sunday some of us attended and photographed a Chamoro wedding.† One of my pictures shows the bride and groom getting ready for toasts. They were pouring tuba from an old U.S. canteen.† (Tuba is a potent concoction distilled from fermented coconut juice.)† One of the dishes served with the wedding feast was a highly spiced curried chicken stew.† I noticed they had included the feet of chicken.† It didnít seem appetizing to me after that.

The pictures on the next page show the happy bride and groom under a large breadfruit tree with the tuba. The lower one shows some of the food preparation.†

Pouring tuba for the

toasting.

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

Cooking for the wedding

feast.

Captured Japanese two-man submarine at

Submariner's rest camp on east side of the island.

Looking at the view from CINCPAC hill.† Even though the war had ended, there still were Japanese soldiers hiding in the Jungle. Some remained there for years.

†††††††††† Since the war was over, everyone was anxious to get home. There was no telling when or how I might get back to the states.† I hadnít been in the service long enough to have the points required for discharge. There wasnít enough transportation available even for those who had the points.† There were movies shown some evenings in an outdoor amphitheater with coconut logs for seats.† But, the time passed slowly, so when I and Grant Hayes heard that two photographers were needed for an inspection tour of the Truk Islands, we volunteered.† This was the only time I volunteered for anything while I was in the service!†

A destroyer had been sent to Truk when hostilities ended, and the Japanese came out by motorboat to sign a surrender document.† However, no U.S personnel had gone ashore.

By the end of September, the Japanese at Truk must have wanted to get back to Japan as least as much as we wanted to go home.† There was no way they could do this on their own. All their ships had been sunk, and they were low on food and medical supplies. They had been blockaded for the past eighteen months. A radio message was sent to Guam, asking for help.

The marines were planning to occupy the islands, but not for another month.† It was decided that an inspection was needed to determine whether or not the garrison was as low on food and medicine as they had indicated by radio.† The purpose of our photography was to bring back photos of the actual conditions.

The cruiser Columbia was chosen to carry out this mission.† We went aboard at Apra Harbor and got under way shortly after.† It was mid-afternoon, and by the next afternoon we were five hundred miles to the southeast with the anchor down just outside the huge lagoon at Truk Islands.† There are some eighty islands in all, with the larger central islands ringed by low coral islands outside.† We were told that sixty of them were occupied by the 40,000 Japanese still there.

Shortly after the anchor was down, someone noticed that sharks were gathering where waste water and sewage was being discharged.† These were large sharks, about ten or twelve feet long.† One of the sailors went below and returned with the biggest fishhook I ever saw.† It was about eight inches long, and he attached a quarter-inch line.† He wraped a piece of newspaper loosely on the hook and dropped it into the outfall.† One of the large sharks immediately grabbed it and was hooked.†† But what to do now?† It looked like the fisherman was trying to hold a horse with a grocery string.† Hauling in, he could pull the shark's head above the surface, but that was about all.† Another sailor brought up a .45 caliber pistol and fired several times into the sharkís head.† It continued to thrash violently, not much affected. Its blood attracted the others, and a savage feeding frenzy began.† In just a minute it was all over, and the sailor hoisted the jaws on board.† That was about all that remained on his hook!

End of section 6, see section 7.