This view of the “Hansen Home Place” shows part of the house and the same barn seen in the one of Hans C. and son Christian grinding corn, but with a silo added, and Thorvald (Christian’s second son, born 1895) can be seen with a bull calf. He appears to be about 12 or 13, so I estimate the picture was made about 1907 or 1908.

The house was remodeled more than once. My father told of the last wing being added to the house when he was young. (This probably was shortly after the death of Hans C.’s daughter Christine and her husband in 1904. Their children, George and Clara Hoegh at about 12 and 10 years old, were taken into the Hansen household and raised with their cousins.) While my family lived there in the late 20’s and early 30’s the walls in several upstairs bedrooms were stripped of several layers of old wallpaper. On the bare plaster were many drawings done in a brownish paint. These showed sailing ships and many quite good drawings of horses. My dad said his grandfather did those for his own amusement when the walls were newly plastered. Dad had been required to help with the plaster mixing and carrying it up to the man who had been hired to do the plastering. He said the plasterer kept calling, “More mud!” before he could get the next batch mixed. I recall feeling sad when the new wallpaper went up and I could no longer see those fascinating drawings. In one of the upstairs rooms there was a pool table built by Hans C. As I recall it had octagonal legs, a regular slate top covered in green felt, and leather pockets. Just like in town! I think he built it for his grandsons. Maybe to keep them out of the pool hall in town? By the time I became acquainted with it, it was no longer in good shape. Some of the pool balls had been left out in the rain and had crackled surfaces. The felt had been torn where someone’s cue had missed the ball. Therefore the balls didn’t always roll in a straight line, but it was fun to try to playing pool anyway.

My Dad told me that when he was a boy he made a bow and arrow. After experimenting with the straightest sticks he could find for arrows, he decided to make an improvement. He took the steel stays from an old umbrella and sharpened the ends on a grindstone. He found he could shoot those arrows right through the barn board he used for a target! Proudly demonstrating this to his grandpa, he found his inventiveness wasn’t appreciated. Hans C. gave him a stern lecture and confiscated the dangerous arrows.

The

The church was located about a mile and a

half from the Hansen farm. It was built

about 1890, and Hans built the steeple. His grandchildren were all confirmed

there, as were my brother and I along with many of our cousins.

The church was located about a mile and a

half from the Hansen farm. It was built

about 1890, and Hans built the steeple. His grandchildren were all confirmed

there, as were my brother and I along with many of our cousins.

There was a parsonage on a one-acre parcel adjacent to the churchyard where the pastor could keep a few chickens and grow his own vegetables. The Lutheran pastors were usually emigrants from Denmark and fitted in well with the mainly Danish community. The pastor and his family were often invited to Sunday dinner after church at member’s homes. (Dinner was always at mid-day, not evening.) My father told of Hans C. getting into religious arguments with the preacher. Apparently the preacher, not as widely traveled as Hans, had some very strong opinions concerning the “heathen” countries. Hans would argue that there were good people there even though they weren’t Christians, much less Lutherans! The preacher must have considered him a terrible heretic.

The small church system worked well for about sixty years, but after that it became difficult to find a pastor willing to live that kind of life. Also, after the depression, many small farms were consolidated into larger ones and there was less population to support a small country church. The congregation moved to a church in town and the old church was torn down. It was feared that with no one living in the parsonage and no caretaker, it would be vandalized.

Hans Christian Hansen died in 1912, and is buried in the Oak Hill cemetery along with his wife, mother-in-law, children and some of his grandchildren and great-grandchildren. My maternal grandparents, George and Bertha Anderson, are also buried there.

-Lyle Hansen

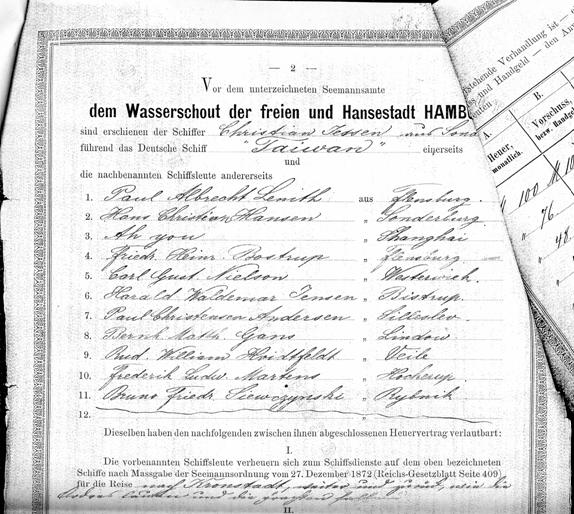

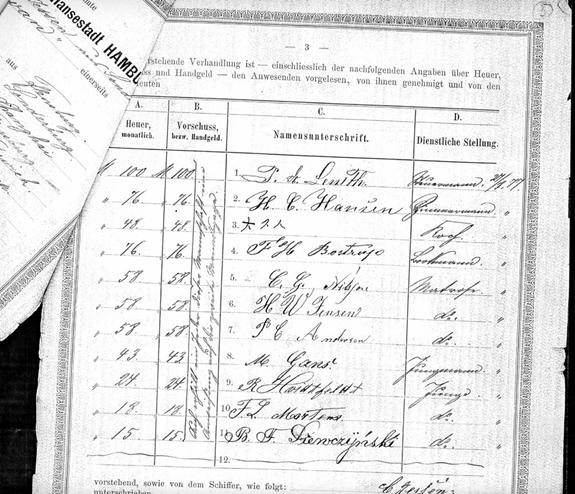

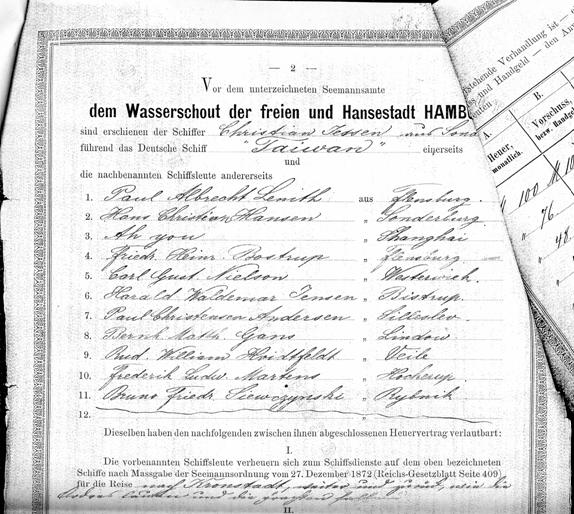

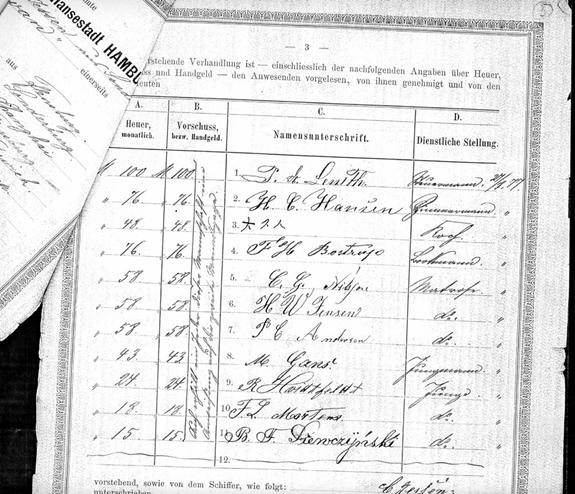

A reproduction of the ship Taiwan's "Musterrolle" (Muster-bill, or Crew list)

Hans Christian Hansen's name is on line 2. The document was signed in the Hamburg shipping office, 25th August, 1877.

Signatures of the Taiwan crew members at the time of their signing on at Hamburg, for "a voyage to Kronstadt, further and return."

Bent Jorgensen of Odense, Denmark, who located this original of this record states: "In the archive in Aabenraa, the bundle containing the Taiwan muster-bill can be found on the shelf: Sonderborg byarkiv, ny afd. XII Monstringsvaesen, 1876-1917, Monstringsruller.

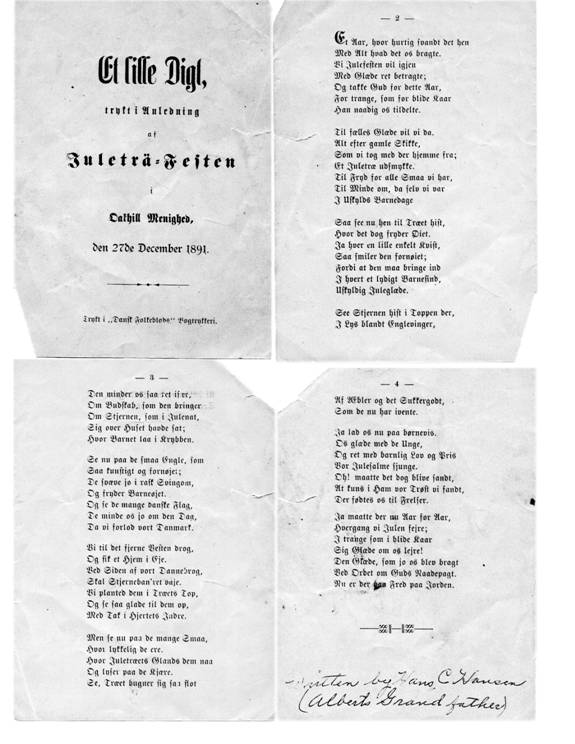

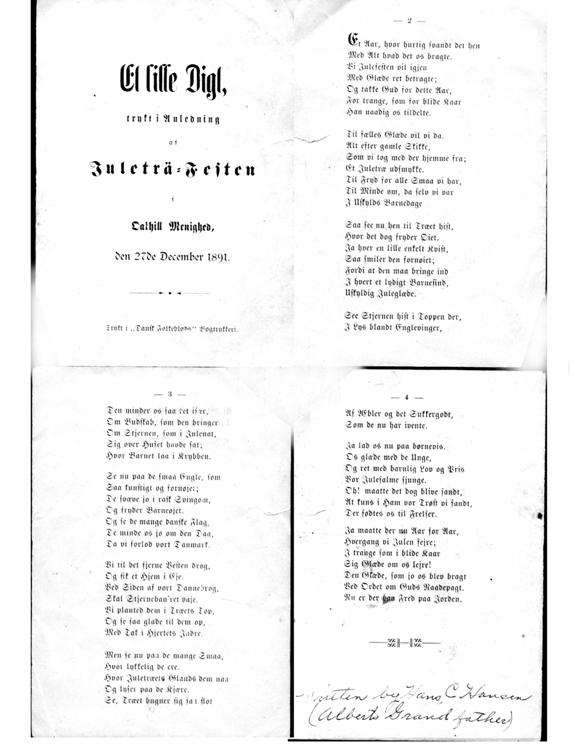

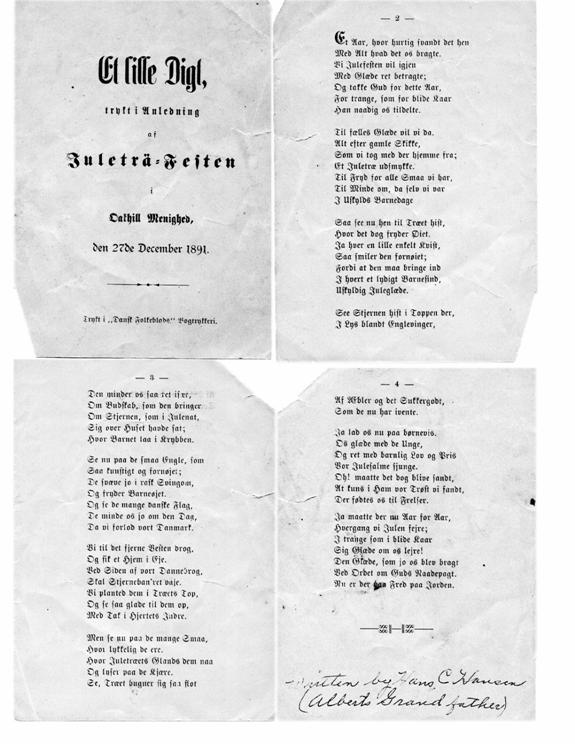

Poem written by Hans C. to commemorate the Christmas Season at Oak Hill. 1891

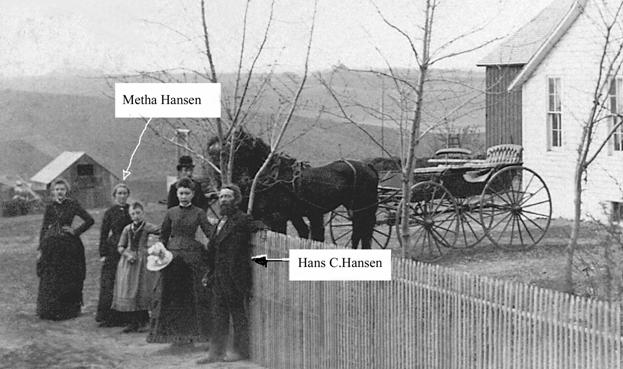

Hans Christian Hansen and his wife Metha.

Photo by Egbert Studio in Atlantic, Iowa. Probably done in the late 1880's.

Hans Christian

Hansen

My

great-grandfather, Hans Christian Hansen was born February 22, 1841 and died

September 12, 1912, ten years before I was born. My grandparents and my father told me stories

about him that fascinated me as a boy, and still do today. I have tried to visualize the times he lived

in during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The industrial revolution was well underway when he sailed out of

Denmark as a young ship's carpenter. In

1868 Bismark's Prussian army with heavy artillery and breech-loading rifles

invaded large parts of Denmark including his home port of Sonderborg while he

was away at sea. The Danes had only

muzzle-loaders and small short range cannon for their defense. Their last point of resistance was at Dybbol,

within sight of Sonderborg. The Danish

soldiers were besieged there for several months but were finally forced into

submission. Another great-grandfather,

my grandmother Hansen's father, Albert Christiansen, was one of the

defenders. He was a native of the nearby

island of Aero.

Danish cannon at Dybbol's monument to the defenders. 1998 photo.

The voyages made

by square-rigged merchant trading ships sailing from Denmark and other European

countries in the 1800's often took them on circumnavigations. Competition from steamships had already

begun. The first regularly scheduled

transatlantic service by steamship began in 1847. The windjammers would be gone from their

homeports for four to five years per voyage. Leaving Europe for the Americas or

Africa, the trade wind route took them around the Cape of Good Hope and then on

to India, Australia and China. While the

Suez canal had opened in 1869, it was not normally used by large sailing

vessels. Attempting to sail in such a

narrow passage without an engine would have been sheer folly. Hiring a tug in addition to the transit fees

would have cut already slim profits too much. The most favored trade wind route

from the orient to Europe was around the horn of South America, passing near

Antarctica, for there was no Panama Canal then.

They probably would not have used it anyway for the same reasons Suez

wasn't practical. There were no radios

for communication or weather information and no mail unless a chance meeting

with another ship homeward bound might carry letters home. Fresh food and water were hard to maintain,

and while there was no refrigeration conditions were probably better than they

were a century earlier when scurvy was prevalent on long voyages. My grandparents used to serve a beef hash

they called lapscous. I assumed it was a

Danish recipe. However I recently read

about British seafaring where lapscous made with potatoes, onions and salt pork

or beef was served on English sailing ships. It was probably a common menu item

on northern European ships.

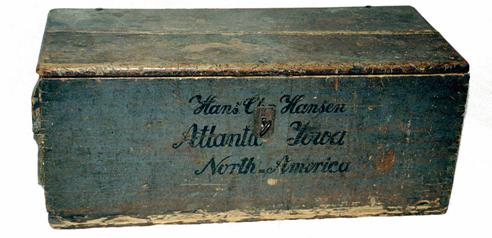

My grandparents gave me

Hans’ sea chest, which accompanied him on his twenty years of seafaring, when

my family left Iowa for Seattle in 1936. Grandma said the old chest had been in

most of major seaports of the world, but not Seattle, so it was fitting that it

go there too. Years later, when I went to Alamogordo, New Mexico, on assignment

for the Boeing Company, it came with our household effects in a moving van.

Later when Boeing reassigned me back to Seattle, it was flown back along with

our other belongings. This came about

because the airplane that brought guided missiles down to New Mexico for test

firings would otherwise have returned empty.

It is a well-traveled keepsake. My grandfather told me it was originally

made from planks about 2 inches thick, but Hans planed it down, by hand, to its

present approximate ¾ inch thickness before he brought his family to America in

1882. This was done to save weight, as

he had to pay shipping costs.

Inside the lid is a drawing of the ship rigged

as a bark, but I had no other information about it until recently. Not even its name. My cousin Fritz Hansen has

done considerable research on our family history for several years and we now

know that his last voyage as a ship's carpenter was made on the

"Tiawan." His signature appears on the list of crew members departing

for a small island near St, Petersburg to pick up cargo to be taken to the

Russian island of Sakhalin north of Japan. My grandfather told me that when his

father left the ship for the last time it sailed out on another voyage and

never returned. This must have been conjecture on the part of my grandfather

unless he was referring to an earlier ship. The record of the Tiawan's voyage

from 1877 through 1881 shows that the ship was idled at Glasgow on November 20,

1881 and the entire crew (eleven men and the captain) was paid off. It was removed from the German registry July

31, 1884 when sold to a Madame Galatola in Genoa. Grandfather probably didn't

know what became of the ship because he emigrated in 1882. The Tiawan was a

brig of 375 registered tons with Sonderburg as her homeport. Register tonnage

refers to the internal volume of freight the vessel could carry. (Approx. 100 cubic feet per ton.) A

forty-foot ketch I built was measured by the US Coast Guard at 5 tons, but its

weight was nearly 15.

"TIA WAN"

This painting of the Tiawan

was done in China and now is in the castle at Sonderburg. It bears a close

resemblance to the drawing inside the sea chest lid. Records show it was built

in 1875 during the German occupation of that part of Denmark. The photo below

shows the Queen of Denmark's yacht tied up beside the Sonderburg castle in

1998.

This painting of the Tiawan

was done in China and now is in the castle at Sonderburg. It bears a close

resemblance to the drawing inside the sea chest lid. Records show it was built

in 1875 during the German occupation of that part of Denmark. The photo below

shows the Queen of Denmark's yacht tied up beside the Sonderburg castle in

1998.

I had been under the impression that Hans

sailed on the same ship for his entire twenty-year career, but since the Taiwan

wasn't that old, there must have been at least one other. This is a record of the ship's muster-bill

with names, homes and pay of the 11 crew members. The captain was one Chr.

Jessen.

Title Name

wages per month Pay in advance

Chief

officer, Paul Albreght Lenith of Flensburg Mark 100 Mark 100

Carpenter, Hans Christain Hansen of Sonderburg Mark

76 Mark 76

Cook, Ah You of Shanghai Mark 48 Mark 48

Boatswain, Friedr. Heinr. Bostrup of Flensburg Mark 76 Mark 76

Sailor, Carl Gustav Nielson of Westerwieck Mark

58 Mark 58

Sailor, Harald Waldemar Jensen of Bistrup Mark 58 Mark 58

Sailor, Paul Christiansen Andersen of

Sillerslev Mark 58 Mark 58

Ordinary seaman,

Bernh. Math. Gans of Lindow Mark 43

Mark 43

Boy, Rud. William Hvidtfeldt of

Vejle Mark 24 Mark 24

Boy, Frederik Ludv. Martens of Hockerup Mark

18 Mark 18

Boy, Bruno Friedr. Siewczynski of

Rybruk Mark 15 Mark 15

The muster bill

doesn't give the captain's pay. The

owners are listed as Peter and Chr. Karberg and the builder as H.H.

Hauschildt. It appears that the muster

was signed at the shipping office in Hamburg August 25, 1877 for a voyage

"to Kronstadt , further and back."

Kronstadt is on an island near St. Petersburg. (the former

Lenningrad.) The boatswain perished at

sea during this voyage and his name was removed from the muster by the

"Imperial vice-consul" at Kronstadt on September 13, 1877. They must

have sailed short-handed back to Copenhagen as the next entry shows boatswain

Hans Galvar Jacobsen from near Roskilde signing on in Copenhagen on December

10, 1877. His pay was less than the

original boatswain, 60 Marks, but was given advance pay of 90 Marks. Bound for

Korsakoff, north of Japan on the Russian island of Sakhalin. The next entry was June 4th, 1878, at the

Hong Kong shipping office. Hans G.

Jacobsen signed off, and the ship was bound for Swatow, to the east of Hong

Kong, again with no boatswain. The next

entry is at Chefoo, October 17, 1878.

Chefoo is in Shantung province across the Yellow Sea and west of the

Korean Peninsula. On October 30, back again at Swatow, the chinese cook Ah Yoo

signed off. On November 8 at the same location Paul Christainsen signed off. A

new chinese cook Tin Fock and a cabin boy signed on for an indefinite period

along with sailor Thomas Asmussen for one year November 18,1878 at Swatow. The

next entry is July 25, 1879, at Hong Kong, where first officer P. Lenith and

the cook signed off. A new first

officer, J.G. Astelmeyer signed on for one year at $35 per month and $35 in

advance. Three days later two sailors, Ludvig Nielson and August Raben, signed

on for one year, and a new cook, Mekshang and boy Ajme signed on for an

indefinite period. The ship was bound

for Foochow, about halfway between Hong Kong and Shanghai. At Foochow on August 15, 1879 the acting German

consul signed "Good for the voyage to Port Elizabeth." (That was in South Africa.) On January 19, 1880 the consul at Port

Elizabeth signed "bound for the voyage to Capetown.” At Capetown on February 6, 1880, the sailors

Ludvig Nielson and August Raben signed off after mutual agreement. One day later James Hunter and Charly Neason

of England signed on and the vessel was "seen good for the voyage from

Capetown in ballast to Calcutta."

However, there is another entry on February 9 to the effect that since

James Hunter did not show up on board, the sailor Alfred Ever, born in England,

was engaged. He signed off in Calcutta,

April 25, 1880. On April 29, Two

sailors, Andreas Jorgensen and Samuel O. Metcalf signed on for the trip back to

Capetown and Captain Jessen reported on May 3 that the missing Bruno Friedr.

Siewczynski fell overboard February 13 on the voyage from Capetown to Calcutta.

By then two of the original crew had perished at sea. An entry at the German consul's shipping

office at Capetown, July 31 1880 states,"Today the sailors Anders

Jorgensen and Samuel O. Metcalf were signing off, they both declare to have

received their wages, and they have no further claims to the ship nor to the

owner." The next entry on August 2,

still at Capetown, has Charley Nielsen signing off. (I assume that is the same

as the Charley Nealson of England who signed on in February at Capetown.) On August 12, Charley Nielsen, born in

Denmark and Carl Seeks born in Prussia, were both engaged for a period of six

months at 3.1 pounds per month, with an advance of 3.1 pounds. The next entry, "Today on August

18,1880, the Captain of the ship, C. Jessen disclosed that the sailor Carl

Seeks from Dolkingen, who signed on on August 12, did not show up on board, and

is therefore considered as a deserter."

On the same day two new sailors, William Esters from England and Syver

Hansen from Norway, signed on for a period of six months. They each received

one months wages in advance, the Englishman

3.10 pounds and the Norwegian 3 pounds.

On the following day the ship was bound for Port Elizabeth from Capetown

with mixed cargo. The next entry at Port

Elizabeth, September 11,1880 is:" Seen and bound for the voyage to Guam in

ballast." (At this point I am some

what mystified, since the next entry, about six weeks later on October 25, says

the ship is "Registered in the consulate of the German Empire at Port

Louis. Bound for the voyage to Hobart

Town with freight." Port Louis is on the British Island of Mauritius in

the Indian Ocean. Perhaps the ship put

in there and found cargo for Tasmania, thereby abandoning the long trip to

Guam. I am doubtful that the ship could

have gone to Guam and returned to Port Louis within the time between entries on

the musterbill.) In the next entry,

December 11, 1880, at Hobart Town, Tasmania, a William Hester was discharged,

and his effects delivered to him. I

assume this was the William Esters from England who signed on in August at

Capetown. On December 16, 1880 still at Hobart Town: "William Felmingham is hereby engaged as

an Ordinary Seaman to serve on board the

Tiawan for six calendar months at 2 pounds per month, and to be discharged at

any port where the service of the ship makes it necessary." A further entry states William Felmingham's

age to be 18, and that he was born in Tasmania. The next entry was made at Port Augusta

(Near Adelaide in southern Australia.)

The date is given as 7-2-01 on the copy of the translation I have. (I

suggest that 01 is a typo which should be 81 and that the date is 7th of

February 1881. Sailing against the trade winds from Tasmania to Port Augusta

plus cargo handling could be expected to take 5-6 weeks from the time the last

entry was made at Hobart. Purpose of the

Australian entry was to enter Jules Anpiais of Nantes, France, engaged as Able

Seaman on a voyage to Capetown. The next

entry at Capetown on May 16, 1881, has Jules Anpiais signing off. May 17 shows the sailor Peter Jensen born in

Denmark, engaged for 3.5 pounds per month for a period of six months. On May 20. still at Capetown, the boy,

William Felmingham, now said to have been born in England instead of Tasmania,

was signed off. On May 25, 1881 the

entry reads, "Seen: Bound for the

voyage in ballast to Ichabo. Cape of

Good Hope, Capetown." Ichaboe is a

"bird island" north of Luderitz in the present Namibia. It was

formerly part of the German protectorate in German Southwest Africa, and a

source of guano. It appears that the

Tiawan went there and loaded a cargo of guano.

The one remaining entry at Glasgow on November 20, 1881 states:

"The present muster-bill is as a matter of the signing off from the entire

crew, hereby by the shipping office declared idle." The forgoing was taken from a translation

furnished by Bent Jorgensen, Fritz's Danish friend in Odense, DK. The anecdotes which follow are those I heard

from my father and grandparents.

A

Derelict Ship

In my

grandparent’s home in Brayton, Iowa, there was a small oil painting of the Last

Supper. Not a great rendition, but the

artist had obviously tried to make it a reasonable copy of the traditional

work. It was about 8 x 10 inches in

size, certainly not more than 10 x 12.

It hung in Aunt Clara’s room.

(Clara was Hans Christian’s daughter and lived at her brother’s home for

a time.) The most interesting thing

about the painting was how it came to be there in that tiny town in the middle

of America.

During one of

his voyages out of Denmark, Hans’ ship came upon another ship in

mid-ocean. The ship was wallowing in the

sea, out of control. A boarding party

was sent out to investigate and offer assistance, Hans a member of the

group. Upon getting aboard, it was

obvious that the ship was abandoned. The

crew had apparently left quite suddenly, for unknown reasons. Plates of uneaten food were on a mess

table. It was a mystery, similar to stories

of the Marie Celeste. I don’t think my

grandparents knew the name of the ship.

They told me the painting was

found in the captain’s cabin, and Hans brought it back to the ship with

him. He brought it home to Sonderborg,

and later carried it to America

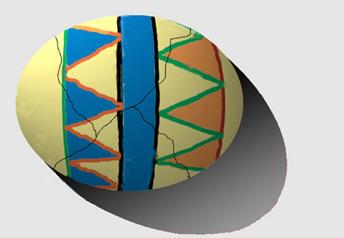

The Ostrich Egg

(Drawn from memory by L. Hansen)

One of the curios in my

grandparent’s home was a hand painted ostrich egg Hans Christian had brought

from Africa. It was a marvelous thing to a small boy to whom the egg of a goose

seemed huge. Over the years and with

all its travels, it had been broken, but glued back together. Recently, while reminiscing with my cousin

Harriet, she told me that she accidentally dropped the egg while playing and

broke it! She must have felt

terrible. She also said she would hide

in the old sea chest when she was a small child.

The Sawfish Snout

Another of the

curiosities at my Grandpa Hansen’s house was the beak, or snout, of a sawfish

which was imbedded in a section of heavy planking, sheathed in copper. This

memento had been removed from the ship’s

bottom when the ship was in drydock.

Hans, being the ship’s carpenter, had cut out the damaged section and scarfed

in a new plank, caulked up the seams, and patched the copper sheathing. Obviously the fish had attacked the ship, but

was trapped by its own wicked weapon, which it had driven full length into the

hull. I can imagine other fish, likely

shark, in a frenzied feeding, cleaning it down until only the fish’s skull

remained. My recollection is that the

beak, with part of the skull still attached, was about two feet long. Sawfish are native to the tropical seas of

America and Africa, and can grow to twenty feet in length. They are known to attack whales.

Carved

Ivory

On a what-not

curio shelf in the parlor of a house on a farm adjoining my great-grandfather’s

farm was an intricately carved piece of ivory. It had been carved form a single

piece of an elephant’s tusk and consisted of a stand supporting a hollow sphere

that had another inside it and still another inside the second. All could rotate freely. The carving had been

brought from China by Hans Christian.

This neighboring farm was owned by Hans R. Hansen. He was not a

relative, but his wife, Anna, was a Hoegh, and a relative by marriage to Hans

Christian. I have been told that Nels P.

Hoegh had corresponded with Hans C., and was instrumental in persuading him to

come to America. With Germany in control

of his part of Denmark, Hans had decided to emigrate. (My father said he had been considering

either Australia or Tasmania.) I surmise

that Hans Christian probably gave the ivory to Nels Hoegh and that Anna Hoegh

Hansen inherited it from him. (Anna was

the organist at the local Oak Hill church when I lived there.) The house at

Hans R’s farm had gas lights. There was

a cistern in the yard outside the house where water was dripped on carbide to

generate acetylene gas. The early

automobiles also used acetylene gas for their headlights.

Oil Paintings from China

Up in the attic

of the “home place” west of Brayton Iowa, there were many things of great

interest to small boys on rainy days.

There was no stairway to get into this attic, just a ladder inside a

closet door, which made getting up there somewhat of an adventure. There was a “shocking machine”. This was a contraption which could deliver

electrical charges of varying intensity to a pair of cylindrical handles which

were to be held by persons suffering from rheumatic pains. It used a dry cell battery of the type then

used in telephones. My bother and I used

to try to see who could take the strongest shock settings! It had been purchased in an effort to

alleviate Han C’s arthritic pains when he was an old man. I doubt that it gave much relief, but the

tingle must have made him hope it did!

There was a Sears and Roebuck 1910 catalog. The variety of merchandise sold mail order at

that time was amazing. You could even

send off for an automobile.

In the fall of

each year our family would go into a

wooded area along the Nishnabotna River we called “the Timber” to gather black

walnuts and hickory nuts. These would be

hulled and then put up to dry on newspaper in the attic. Sometimes we were allowed to take a hammer

and a flat iron for an anvil up to crack those delicious nuts.

There were old

copies of magazines stored up there. How

I wish they had been saved until now!

One was a copy of Harper’s in which the entire issue was devoted to the

sinking of the Titantic. It was lavishly

illustrated with drawings and had several eyewitness accounts of the

disaster. There were early issues of the

Scientific American. Off in one corner were two framed oil portraits. These were of Hans Christian and Metha and

had been painted in China. I used to look at them and try to know more about my

great-grandparents. I think the artist

probably did them from photographs Hans C. carried with him. Certainly his wife was not with him on those

voyages. I had forgotten all about those

paintings until some time in the 1950’s, when my grandmother sent her photo

album out to Seattle. The old paintings

had been cut out of their frames and scotch-taped to pages in her photo album! The canvases have become quite fragile, and

the paint has cracked badly. There is a

bad tear in the canvas of Metha’s portrait.

I have made photographic copies, scanned them into my computer and spent

hours retouching the myriad cracks in the paint and the rip in the canvas. I have not been completely successful, but

have reproduced them here. Wasn’t Metha

a good looking young woman?

Another

interesting item stored in the attic was a spinning wheel. It was fun to pump the treadle and watch the

wheel spin. I don’t know if it was

Metha’s or if it may have been her mother’s, who emigrated with Hans C. and his

family. My brother’s daughter Suzi has it now, and is shown using it below.

A Chinese Banquet

One

of the stories my Dad told me was an account of a very sumptuous feast given by

a Chinese merchant who was trading with my Great-grandfather’s ship. Apparently the trade had been profitable, and

the merchant, showing his gratitude, invited the whole ship’s company to a

lavish banquet. Those sailors had never

seen such food before. As each of the

many courses was served they tried to learn what it was they were eating. Soups, chicken and pork dishes, each seemed

to have been prepared in a more delicious way than the preceding one. But the most delicious one of all was a

mystery. The gracious host was not

helpful in explaining the contents, but he offered more, which was gratefully

accepted. Continued questioning of the

host during the meal gave no answer.

Finally, after they had left the banquet hall, they learned that the

main ingredient of the fabulous dish had been rat embryos!

The

Sargasso Sea

The U.S.

purchased the Danish Virgin Island from Denmark during World War I for use as a

coaling station. My father used to tell

of his grandfather being bemused by the fact that the black men he met there

spoke perfect Danish! On one of the

voyages outbound from Denmark the ship was blown off course and was becalmed in

the Sargasso Sea. Whether bound for

South America or perhaps the then Danish Virgin Islands, I do not know. At any rate, the ship lay in the heat among

the Sargasso weed day after windless day.

I imagine the seamen had to dip buckets into the water to pour on the

decks to cool the ship and to keep the seams in the deck planking from cracking

open. On this particular voyage the

Captain’s wife had come along. It was

not uncommon for the captain’s wives to accompany their husbands. The lone female aboard became nervous and

upset at being in such an unpleasant place for so many days. It seemed to bring out the shrew in her. Her nagging became more and more severe with

the dawn of each day as they waited for the wind. “There must be something you can do to get

away from this dreadful place.” “You

should change the sails to catch more wind.”

“You’re the captain, why don’t you do SOMETHING?” Now the captain was a patient man, perhaps

even reasonable. But the continual

litany of abuse over a condition beyond his control ended his patience. “Do something” she had commanded. So he did.

Burly seamen were called on deck and the protesting wife was bound into

her rocking chair. Then from a block

rigged on a spar overhanging the water, chair and wife were dropped into the

water. Hauled up, the sputtering woman

heaved more abuse on her husband. (Could

you blame her?) The process was repeated

twice more before the poor woman agreed to stop nagging! The story was that the wind came up the next

day and the ship was able to continue its journey. The vessel’s master was not nagged again!

Handling

Cargo in the Orient

Hans C.’s ship

sailed with many different cargos, and grain was one of them. One of the anecdotes related to me was the

system for loading or unloading grain.

At one oriental port, the stevedores were all women, moving the baskets

rapidly in rhythm with songs they sang.

It was a hot tropical climate and the work was hard, causing the workers

to perspire heavily. Then, when it was

time for a lunch break, they removed all their clothing and jumped into the sea

to wash and cool off. Needless to say

the sailors were ogling! According to

what my father was told, after a few days of loading it became so commonplace

that the sailors hardly noticed. I

wonder about the truth of that.

On another

occasion, the cargo was wooden kegs of gunpowder. As these were rolled along the deck to the

hatch for stowing below in the cargo hold, some of the kegs spilled

powder. The iron hoops that held the

keg’s staves together were loose, allowing powder to escape. Being the ship’s carpenter, it was up to Hans

C. to check and drive all the loose hoops tight. He had to be careful to keep his hammer from

making the tiniest spark, as the whole ship could have been blown up. He placed canvas between his hammer and the

metal hoops. He told my dad that no one

in the crew was happy to sail with that cargo, as they were not allowed to

smoke their pipes until all the powder was removed at the next port!

Another time in

China it seems they were anchored in a large river, possibly the Yangtze at

Shanghai, during a terrible flood. When

it was time to raise the anchor a dead man was found entangled on the

cable. It appeared that he had drowned

in the flood and his body washed downstream eventually catching on the anchor

chain.

Hans also told

of visiting the Great Wall, which he described as being large enough to drive a

team of horses along the road at its top.

Around the Horn

Sailing a

square-rigged ship around the South America’s Cape Horn was never an easy

task. The currents are strong, and

weather is treacherous, with blustery winds, rain and snow. In that environment the seamen going aloft to

take in or let out sail literally took their lives in hand. High up in the

rigging the old saying of one hand for the ship and one for yourself was always

the rule. Under those conditions and

with the ship heaving through heavy seas, one mistake would be the last. A missed foot-rope or numbed slippery fingers

could send a man to his death. The ship

could not come about quickly and try to rescue a man overboard. With the strong wind the ship would be miles

downwind before any such maneuver could be executed, even if there was enough

sea room to permit it. Also, with the

square-rigger’s lack of ability to sail upwind, how could they expect to return

and search for the missing man? The

answer is they could not. Many sailors

couldn’t swim, and none wore life jackets so far as I am aware. No one had invented survival suits. Water temperatures of 50 degrees or below

usually result in death within less than an hour, sometimes in just a few

minutes. If a man went overboard while

sailing around the Horn, he was dead. My

father told me Hans C. witnessed such an event.

How would you feel when one of your shipmates fell from 100 feet or

higher into that cold and unforgiving sea?

There is nothing in the record of the Tiawan's four year voyage to

indicate anyone lost going around the horn.

We can't be sure from the record in hand that they went around the Horn

on that voyage. It does state that the Bos'n perished at sea on the first leg

of the voyage out of Hamburg when on the way to Kronstad. (near St.

Petersburg) And another man, the young

sailor Bruno Siewczynski, was lost overboard in the Indian Ocean on a trip to

Calcutta out of Cape Town.

Australia and Tasmania

When Hans C.

decided to leave Denmark, he considered going to Tasmania or Australia. He spoke of grapefruit and orange trees with

fruit so plentiful it laid thick on the ground.

This was probably Australia, as I am not sure citrus fruit was grown in

Tasmania. Nels Hoegh persuaded him to

come to America and settle in Iowa.

After coming to America, he probably wondered how things might have been

had he gone elsewhere. According to my

father, he often spoke about Australia and Tasmania nostalgically.

Emigration

Hans C.

emigrated in 1882 from what was then Germany but had been Denmark until

1868. (His home town of Sonderborg was

finally returned to Denmark in 1920, as

part of the settlement of World War I.)

Times were hard in that part of Denmark.

He didn’t want his children forced to learn only German in school. There must have been considerable planning

and preparation for the trip. Passports

and paperwork had to be managed. Besides

he, his wife and three children, there was his mother-in-law in the party as

well. Recall that he planed down the

heavy sea chest by hand to save weight?

That had to take a day or two! My

grandfather told me his father made a canvas moneybelt to hold his life’s

savings of gold coins and wore it day and night during the voyage. My cousin Frederick has done considerable

genealogical research and has found copies of the emigration papers. He even found that the name of the small

steamship that brought them across the Atlantic was the “Herder”. A neat Danish script hand painted on the

front of the sea chest gives the destination.

They must have

come by train from New York to Iowa, and by today’s standards, it wasn’t a

swift journey. It may have seemed

lightning fast, in comparison to the ocean crossing. Did they go through Chicago? How many times did they have to change from

one railroad company to another? There

must have been a joyous reunion with Nels Hoegh upon finally arriving in

Atlantic. I have located a photograph

of Hans C. and Metha with some unidentified persons on what is said to have

been his first home in America. Could

the man in the stylish derby hat be Nels Hoegh?

I suspect this farm was rented for a time

until he purchased his own, which was located only two or three miles away.

The 120 acre

farm he purchased was raw land in the low rolling hills of southwestern Iowa. Much of it had not seen the plow. (It may be interesting to note that one

branch of the Mormon trail was across the road from the southern boundary of

that land. Deep ruts from their wagon

trains were still in evidence when I was a boy.) Scrub oak grew there and had to be

cleared. It took years to get all his

land under cultivation, and there was a meadow that had never been plowed even

during the time I lived there from 1926 to 1933. A small creek flowed through

it and the well with its windmill was located there. The windmill pumped water up the hill to a

large storage tank to keep the house and livestock supplied.

Christian Hansen and his father, Hans C., grinding corn beside the first barn.

So

far as I know, the house, two barns and other outbuildings on the new farm were

all built by Hans C. He had brought his carpenter tools along. I remember the tools in my grandfather’s shop

in his garage at Brayton. My uncle Frank

donated them to a newly established museum in Brayton in the mid-fifties when

he left Iowa to move to Seattle. Most of

the tools were made of wood, with steel blades inset. There were augers of different sizes for boring

holes up to about two inches in diameter.

Each had its own permanently fastened handle. There was also a brace and bit for smaller

holes, the brace itself of wood, and the steel bit was flat with sharpened

angles on its two opposite sides. There were several wooden planes, very well

made. Records found by my cousin Frederick show that Hans C.’s father came to

Sonderborg from the Baltic island of Bornholm, and that he was also a ship’s

carpenter. Might some of those tools

have been his father’s? I have inherited

some of the tools my father used as a shipwright and carpenter, so why not?

This view of the “Hansen

Home Place” shows part of the house and the same barn seen in the one of Hans

C. and son Christian grinding corn, but with a silo added, and Thorvald

(Christian’s second son, born 1895) can be seen with a bull calf. He appears to be about 12 or 13, so I

estimate the picture was made about 1907 or 1908.

The house was remodeled more than once. My father told of the last wing being added to the house when he was young. (This probably was shortly after the death of Hans C.’s daughter Christine and her husband in 1904. Their children, George and Clara Hoegh at about 12 and 10 years old, were taken into the Hansen household and raised with their cousins.) While my family lived there in the late 20’s and early 30’s the walls in several upstairs bedrooms were stripped of several layers of old wallpaper. On the bare plaster were many drawings done in a brownish paint. These showed sailing ships and many quite good drawings of horses. My dad said his grandfather did those for his own amusement when the walls were newly plastered. Dad had been required to help with the plaster mixing and carrying it up to the man who had been hired to do the plastering. He said the plasterer kept calling, “More mud!” before he could get the next batch mixed. I recall feeling sad when the new wallpaper went up and I could no longer see those fascinating drawings. In one of the upstairs rooms there was a pool table built by Hans C. As I recall it had octagonal legs, a regular slate top covered in green felt, and leather pockets. Just like in town! I think he built it for his grandsons. Maybe to keep them out of the pool hall in town? By the time I became acquainted with it, it was no longer in good shape. Some of the pool balls had been left out in the rain and had crackled surfaces. The felt had been torn where someone’s cue had missed the ball. Therefore the balls didn’t always roll in a straight line, but it was fun to try to playing pool anyway.

My Dad told me

that when he was a boy he made a bow and arrow.

After experimenting with the straightest sticks he could find for

arrows, he decided to make an improvement.

He took the steel stays from an old umbrella and sharpened the ends on a

grindstone. He found he could shoot

those arrows right through the barn board he used for a target! Proudly demonstrating this to his grandpa, he

found his inventiveness wasn’t appreciated.

Hans C. gave him a stern lecture and confiscated the dangerous arrows.

The

Oak Hill Church

The church was located about a mile and a half from the Hansen

farm. It was built about 1890, and Hans

built the steeple. His grandchildren were all confirmed there, as were my

brother and I along with many of our cousins.

The church was located about a mile and a half from the Hansen

farm. It was built about 1890, and Hans

built the steeple. His grandchildren were all confirmed there, as were my

brother and I along with many of our cousins.

There was a parsonage on a

one-acre parcel adjacent to the churchyard where the pastor could keep a few

chickens and grow his own vegetables.

The Lutheran pastors were usually emigrants from Denmark and fitted in

well with the mainly Danish community. The pastor and his family were often

invited to Sunday dinner after church at member’s homes. (Dinner was always at mid-day, not

evening.) My father told of Hans C.

getting into religious arguments with the preacher. Apparently the preacher, not as widely

traveled as Hans, had some very strong opinions concerning the “heathen”

countries. Hans would argue that there

were good people there even though they weren’t Christians, much less

Lutherans! The preacher must have

considered him a terrible heretic.

The small church

system worked well for about sixty years, but after that it became difficult to

find a pastor willing to live that kind of life. Also, after the depression, many small farms

were consolidated into larger ones and there was less population to support a

small country church. The congregation

moved to a church in town and the old church was torn down. It was feared that

with no one living in the parsonage and no caretaker, it would be vandalized.

Hans Christian

Hansen died in 1912, and is buried in the Oak Hill cemetery along with his

wife, mother-in-law, children and some of his grandchildren and

great-grandchildren. My maternal grandparents, George and Bertha Anderson, are

also buried there.

-Lyle

Hansen

A

reproduction of the ship Taiwan's "Musterrolle" (Muster-bill, or Crew

list)

Hans Christian

Hansen's name is on line 2. The document

was signed in the Hamburg shipping office, 25th August, 1877.

Signatures of the Taiwan crew members at the time of their signing on at Hamburg, for "a voyage to Kronstadt, further and return."

Bent Jorgensen of Odense, Denmark, who located this original of this record states: "In the archive in Aabenraa, the bundle containing the Taiwan muster-bill can be found on the shelf: Sonderborg byarkiv, ny afd. XII Monstringsvaesen, 1876-1917, Monstringsruller.

Poem written by Hans Christian Hansen to commemorate the Christmas Season at the Oak hill church, 1891