|

The Life of Hans Christian Hansen |

||

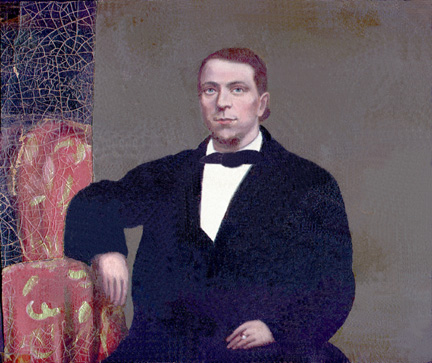

Oil Painting of Hans C., while visiting China By Lyle Hansen

I never had the opportunity to meet my great-grandfather, as he died five years before I was born. My father and grandparents told anecdotes about him that fascinated me as a boy, and still do today. I have tried to visualize the times he lived in during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The industrial revolution was beginning when he was a young ship’s carpenter sailing out of Denmark. In 1868 Bismark’s Prussian army with heavy artillery and breech-loading rifles invaded and occupied a large part of Denmark including his home port of Sonderborg while he was away at sea. The Danes were still using muzzle-loaders and had only small canons for their defense. Their last point of resistance was at Dybol, within sight of Sonderborg. The Danish soldiers were besieged here for several months but finally were blasted into submission. (Another great-grandfather, my grandma Hansen’s father, Albert Christiansen, who came from the nearby island of Aero, was one of the defenders.) The voyages made by square-rigged merchant ships out of Denmark and other European countries in the 1800’s often took them on circumnavigations. These vessels went wherever there was cargo to be traded. Competition from steamers had already begun. (The first regular scheduled transatlantic service by steamship began in 1847.) The square-riggers would be gone from four to five years at a time. They would leave Europe for the Americas or Africa, then around the Cape of Good Hope and on to India, Australia and China. While the Suez canal had opened in 1869, it wasn’t normally used by large sailing vessels. Attempting to sail in such a narrow passage without an engine would have been sheer folly, and hiring a tug in addition to paying transit fees would have cut the slim margin of profit too much. Relying on the trade winds, the return trip necessitated coming around the horn of South America, passing near Antarctica, for the Panama Canal hadn’t been built. They probably would not have used it anyway, for the same reasons that made Suez impractical. There were no radios for weather information, no mail unless a chance meeting with another ship going the opposite direction might carry letters home. Fresh food and water were hard to maintain, and while there was no refrigeration, conditions probably were better than a century earlier when scurvy was common on shipboard. Lime juice for the British sailors and sauerkraut for the Germans! I suspect the Danes had their share of sauerkraut. My grandparents used to make a beef hash with potatoes and onions. They called it lapscous. I had always assumed it was a Danish dish. Several years ago I was reading about British seafaring and learned that lapscous was served to English crews and made from salt beef or pork with potatoes and onions. It may have been a common item on northern European ships.

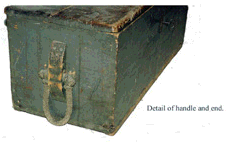

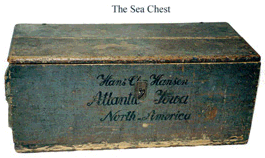

I have in my possession Hans’s sea chest, which accompanied him on his voyages. My grandfather said that it was originally made of planks about two inches thick, but Hans planed it down, by hand, to its present approximate ¾ inch thickness before he brought his family to America. This was done to save weight, as he had to pay for the weight of everything shipped.

In my grandparent’s house in Brayton Iowa there was a small oil painting of the Last Supper. Not a great rendition, but the artist had obviously tried to make it a reasonable copy of the traditional work. It was about 8 x 10 in size, certainly no more than 10 x 12. This was displayed in Aunt Clara’s room. The most interesting thing about it was how it came to be there in that tiny town in the middle of America. During one of his voyages out of Denmark, my great-granddad’s ship came upon another ship in mid-ocean. The ship was wallowing in the sea, out of control. A boarding party was sent out to investigate and offer assistance, Hans Christian with the group. Upon getting on deck it was obvious that the vessel had been abandoned. There was no one on board. The crew had left quite suddenly, for an unknown reason. Plates with uneaten food were on the table. A mystery, similar to stories of the Marie Celeste, but I have no knowledge of the vessel’s name. The painting was found in the captain’s cabin, and Hans brought it back to the ship with him. He brought it home to Denmark, and later carried it to America.

One of the curiosities in my grandparent’s house was a hand painted ostrich egg Hans Christian had brought from Africa. It was a marvelous thing to a small boy to whom the egg of a goose seemed huge. Over the years and with all its travels, it had been broken, but glued back together again. When I was reminiscing with my cousin Harriet just a year ago, she told me she accidentally dropped the egg while playing and broke it! She must have felt terrible. She also said she used to hide in the old sea chest when she was a small child.

Another of the curiosities at Grandpa Hansen’s house was the beak of a sawfish imbedded in a section of heavy planking, sheathed in copper. My recollection is that the beak, with part of the fish’s skull still attached, was about two feet long. This memento had been removed from the ship’s bottom when in dry-dock. Hans, being the ship’s carpenter, had cut out the damaged section and scarfed in a new plank, caulked up the seams, and patched the copper sheathing. Obviously the fish had attacked the ship, but was trapped by its own wicked weapon, which was driven its full length into the hull. I can imagine other fish, perhaps shark, in a frenzied feeding, cleaning it down to the skull, where it remained until discovered in dry-dock.

One of the farms adjacent to my great-grandfather’s farm in Iowa was owned by Hans R. Hansen. He was not a relative, but his wife, Anna, was a Hoegh, and a relative by marriage to Hans Christian. I have been told that Nels P. Hoegh had corresponded with Hans C., persuading him to come to America. With Germany in control of his part of Denmark, he was ready to leave. My father said he had considered either Australia or Tasmania. So that is how a certain piece of very intricately carved ivory came to be on the whatnot curio shelf in the parlor of Hans R.’s house. It was one of those pieces carved from a single part of an elephant tusk which had one hollow sphere inside another with a third carved hollow sphere inside that. All could rotate freely. Hans C. had brought it from China and given it to the Hoegh’s, possibly Nels, and it was later inherited by Anna. Another interesting thing about Hans R’s home was that it had gas lights. There was a cistern in the yard outside the house where a valve could be opened drip water on carbide and generate acetylene gas. A pressure gauge needed to monitored in case the pressure rose too high. The early automobiles also used acetylene for their headlamps.

Up in the attic of the “home place” west of Brayton, there were many wonderful things to be found by small boys on rainy days, one of which was a “shocking machine.” This contraption delivered electrical charges of varying intensity to a pair of cylindrical handles which were to be held by persons suffering from rheumatic pains. It used a dry cell battery of the type then used in telephones. My brother and I used to try to see who could take the stronger settings! It had originally been purchased in an effort to alleviate Hans C.’s arthritic pains when he was an old man. I doubt that it gave much relief, but the tingle must have made him hope it might! In addition to this machine, existed an old Sears and Roebuck catalog from 1910. The variety of merchandise sold mail order at that time was amazing. You could even send off for an automobile! In the fall of each year our family would go into a wooded area along the Nishnabotna river we called “the Timber” to gather black walnuts and hickory nuts. These would be hulled and then put up in the attic on newspaper to dry. So we could take a hammer up there, and using a flat iron for an anvil, crack and eat those wonderful nuts. There were old copies of magazines that had been considered too valuable to destroy. How I wish they had been saved until now! One issue, in particular, I wish had been saved, a copy of Harper’s devoting an entire issue to the sinking of the Titantic. It was lavishly illustrated with drawings and filled with eyewitness accounts of the disaster. There were early issues of the Scientific American.

I had forgotten all about those paintings until some time in the 1950’s. That was when my grandmother sent her photo album out to Seattle. The two paintings had been cut out of their frames and scotch-taped to the pages in her album! As a result, the canvas is now very fragile, and the paint has cracked badly. There is a bad tear on one of the canvases. I have made photographic copies and spent hours on the computer trying to retouch the myriad cracks in the paint and the rip in the canvas. I have not been completely successful. They are reproduced here. Wasn’t Metha a good looking woman?

One of the stories may Dad told me was an account of a very sumptuous feast given by a Chinese merchant who was trading with my great grandfather’s ship. Apparently the the trade had been profitable, and the merchant, showing his gratitude, had invited the whole ship’s company to a lavish banquet. Those sailors had never seen such food before. As each of the many courses was served they tried to learn what it was they were eating. Soups, chicken and pork dishes, each seemed to have been prepared in a more delicious way than the preceding one. But the outstandingly most delicious one of all was a complete mystery. Their gracious host was not helpful in explaining the contents, but he offered more, which was gratefully accepted. Continued questioning of the host during the meal gave no answer. Finally, after they left the banquet hall, they learned that the main ingredient of that fabulous dish had been rat embryos!

The U.S. purchased the Danish Virgin Islands, during World War I, for use as a coaling station by the U.S Navy. My father used to tell of his grandfather being in the Virgin Islands. He was bemused by the fact that the black men he met there spoke perfect Danish! Hans C. may have been bound for the Danish Virgin Islands on one outbound voyage from Denmark when the ship was blown off course and was becalmed in the Sargasso Sea. The ship lay in the heat among the Sargasso weed, day after windless day. I imagine that the seamen had to dip buckets into the water to pour on the decks to cool the ship and to keep the seams in the deck planking from cracking open. On this particular voyage the Captain’s wife had come along. Apparently it was not uncommon for the captain’s wives to sail with their husbands. At any rate the lone female aboard became nervous and upset at being in such an unpleasant place for so many days. It seemed to bring out the shrew in her. Her nagging became more and more severe with the dawn of each day as they waited for the wind. “There must be something you can do to get out of this dreadful place!” “You should change the sails to catch more wind!” “You’re the captain, why don’t you do SOMETHING?” Now the captain was a patient man, perhaps even reasonable. But the continual litany of abuse over a condition beyond his control ended his patience. “Do something” she had commanded. So he did. Burly seamen were called on deck and the protesting wife was bound into her rocking chair. Then, from a block rigged on a spar overhanging the water, chair and wife were dropped into the water. Hauled up, the sputtering woman heaved more abuse on her husband. (Could you blame her?) The process was repeated twice more before the poor woman agreed to stop nagging! The story was that the wind came up the next day and the ship was able to continue its journey. The vessel’s master was not nagged again!

The ship sailed with many different cargos, but grain was one of the most common. One of the anecdotes related to me was the oriental system for loading or unloading grain. Baskets were passed from person to person in a long human chain reaching from the hold of the ship to the dock or in some cases a lighter. At one oriental port, the stevedores were all women, and moved the baskets quite rapidly, singing as they worked. It was in a hot tropical climate and the work was hard, causing the women to perspire heavily. Then, when it was time for a lunch break, they lined up at the ship’s rail and removed their clothes and jumped into the sea to wash and cool off. Needless to say, the sailor’s were ogling! According to what my father was told, after a few days of loading it had become so commonplace that the sailors hardly noticed. I wonder about the truth of that. On another occasion, when the cargo was gunpowder, it came in wooden kegs. These were rolled up planks to the deck, and then rolled to the hatch and brought down into the hold. A problem came up when some of the kegs spilled powder as they were being rolled. The steel hoops that held the staves together were not tight, and cracks between the staves let the powder escape. Hans C. was given the task of making sure the hoops were driven down tightly before the kegs were stowed. He had to be careful to keep his hammer from making the tiniest spark. He placed cloth between his hammer and the metal hoops. He said that no one in the crew was happy when sailing with that cargo, since they were not allowed to smoke their pipes until the powder could be unloaded at the next port! Another time in China they were anchored in a large river, probably the Yangtze at Shanghai, during a terrible flood. When it was time to raise the anchor, a dead man was found entangled on the anchor chain. He had apparently been drowned during the flood and his body washed downstream eventually catching on the chain. He also told of visiting the Great Wall, which he described as being large enough to drive a team of horses along the road at its top.

When Hans C. decided to leave the sea and emigrate from Denmark, he had considered Australia or Tasmania. He spoke of grapefruit and orange trees laden with fruit so plentiful it lay thick on the ground. This was probably in Australia, as I am not sure citrus fruit grows in Tasmania. Nels Hoegh persuaded him to come to America and settle in Iowa. After coming to America, he probably wondered how things might have been had he gone elsewhere. According to my father, he often spoke nostalgically about Tasmania and Australia.

Sailing a square-rigged ship around the south end of South America was not an easy task. The currents are strong, weather is treacherous, blustery winds, rain and snow are common. In this environment seamen who had to go aloft to take in or let out sail literally took their lives in hand. High up in the rigging the old saying of one hand for the ship and one for yourself was always the rule. Under those conditions, and with the ship heaving through heavy seas, one mistake could be the last. A missed footrope or numbed slippery fingers could send a man to his death. The ship could not come about quickly to rescue the man. With the strong wind moving the ship at fifteen or more knots it would be far downwind before any such maneuver could be executed, even given sea room enough to permit coming about. And then, with the square-rigger’s lack of ability to sail upwind, how could they ever expect to return to search for the missing man? The answer is, they couldn’t. Many sailors couldn’t swim, none wore life jackets so far as I am aware. No one had invented survival suits. Water temperatures of 50 degrees or below usually result in death within less than an hour, sometimes in just a few minutes. If a man went overboard while sailing around the horn, he was dead. My father told me Hans C. witnessed such an event at least once in the several times he sailed around the horn. How would you feel when one of your shipmates fell from 100 feet or higher into that cold and unforgiving sea?

There must have been considerable planning and preparation for the trip. Passports and paperwork had to be managed. Besides his wife and two children, there was his mother-in-law in the party as well. Recall that he planed down the heavy searches by hand to save weight? That had to take a day or two! My grandfather told me, his father made a canvas

money-belt to hold his life’s savings of gold coins and

wore it day and night during the voyage. My cousin, Frederick

(Fritz), has done considerable genealogical research and came

up with copies of the emigration papers. He even found that

the name of the small steamship that carried them to America

was the “Herder.” Neatly painted Danish script on the sea

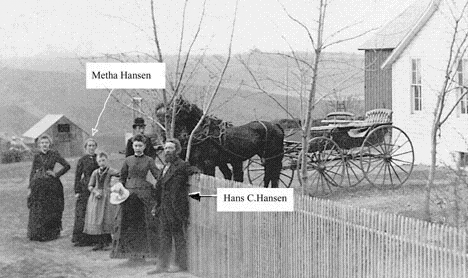

chest gives his destination. They must have taken the train from New York to Atlantic, and by today’s standards, it wasn’t a swift journey. It probably seemed lightning fast, in comparison to the ocean crossing. Did they go through Chicago? How many times did they have to change from one train to another? Arriving finally in Atlantic, Nels Hoegh was located and a joyous reunion must have been celebrated. I have located a photograph of Hans C. and Metha with unidentified persons on his first farm in Iowa. I suspect it was rented for a time until he found and purchased his own, which was nearby. So far as I know, the house, two barns, and outbuildings were all built by Hans C. He had brought his carpenter tools along. I remember them in the shop in my grandfather’s garage in Brayton.

The 120-acre farm he purchased was raw land in the rolling low hills of southwestern Iowa. There was much of it that had not seen the plow. Scrub oak grew in places. It may be interesting to note that one branch of the Mormon trail was across the road from the southern boundary of that land. The deep ruts from their wagon trains were still in evidence when I was a boy. It took years to get all his land under cultivation, and there was a meadow which had never been completely plowed even during the time I lived there. A small creek flowed through it, and the well with its windmill was located there. The windmill pumped water up the hill to a large storage tank to keep the house and the livestock supplied. My father told of the last wing

being added when he was a young teenager. This

probably took place when George Hoegh and his

sister came to live with the Hansen family after their

parents died. While my family was living there the walls

in several upstairs bedrooms were stripped of the several

layers of old wallpaper and on the bare plaster were

many drawings done in a brownish paint. These showed sailing

ships and many quite In one of the upstairs rooms of that house, there was pool table built by Hans C. As I recall, it had tapered octagonal legs, a regular slate top covered in traditional green felt, and leather pockets. Just like in town! I think he built it for his grandsons. Maybe to keep them out of the pool halls in town? By the time I became acquainted with it was no longer in good shape. Some of the pool balls had been left out in the rain and had crackled surfaces. The felt had been torn where someone’s cue had missed the ball. Therefore the balls didn’t always roll in a straight line. But it was fun to try anyway. My dad told me that when he was a boy he made himself a bow and set of arrows. After experimenting with the straightest sticks he could find for arrows, he decided to make an improvement. He took the steel stays from an old umbrella and sharpened the ends on the grindstone. He found he could shoot these arrows right through the board he was using for a target! Proudly demonstrating this to his grandpa, he found his inventiveness wasn’t appreciated. Hans C. gave him a stern lecture and confiscated the dangerous arrows.

The church was located about a mile and a half from the Hansen farm. It was built about 1890, and Hans C. built its steeple. My brother and I were both confirmed there. There was a parsonage on a one-acre parcel adjacent to the churchyard where the pastor could keep a few chickens and grow his own vegetables. The Lutheran pastors were usually emigrants from Denmark and fitted in well with the mostly Danish community. The pastor and his family would often be invited for Sunday dinner after church at member’s homes. (Dinner was always in mid-day, not evening.) My father told of Hans C. getting into religious arguments with the preacher. Apparently the preacher, not as well traveled as Hans, had some very strong opinions concerning the “heathen” countries. Hans would argue that there were good people who lived there, even though they were not Christians, much less Lutherans! The preacher must have considered him a heretic. The small church system worked well for about sixty years, but after that it became difficult to find a pastor willing to live that kind of a life. Also, after the depression, the small farms began to be consolidated into large ones and there was less population to support a small local church. The congregation moved into town and the church was torn down. It was feared that with no one living in the parsonage and no caretaker, it would be vandalized. Hans C. died in 1917, and is buried in the Oak Hill cemetery with his wife, mother-in-law, two children, and some of his grandchildren and great-grandchildren. My maternal grandparents, George and Bertha Anderson, are also buried there. |

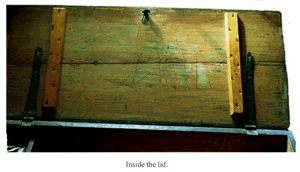

Inside the lid is a drawing of his ship,

rigged as a bark, but I have not much information about

the ship. Not even its name. My grandfather said that after

his father left the ship for the last time and it sailed

out on another trip around the world, it never returned.

What happened to it, sunk in a storm or shipwrecked

on some remote shore, no one ever knew. My grandparents

gave me the sea chest when my family left Iowa for

Seattle in 1936.

Inside the lid is a drawing of his ship,

rigged as a bark, but I have not much information about

the ship. Not even its name. My grandfather said that after

his father left the ship for the last time and it sailed

out on another trip around the world, it never returned.

What happened to it, sunk in a storm or shipwrecked

on some remote shore, no one ever knew. My grandparents

gave me the sea chest when my family left Iowa for

Seattle in 1936.  Grandma said the old chest had been in

most of the major seaports of the world, but not in Seattle,

so it was fitting that it go there too. Years later,

when I went to Alamogordo, New Mexico, on an assignment

for the Boeing Company, it was brought there with

our household effects in a moving van. Then, when Boeing

reassigned me back to Seattle, it was flown back to Seattle

along with our other belongings. This came about because

the airplane used to bring the guided missiles down to

New Mexico for test firings were otherwise empty when returning.

It is a well-traveled keepsake.

Grandma said the old chest had been in

most of the major seaports of the world, but not in Seattle,

so it was fitting that it go there too. Years later,

when I went to Alamogordo, New Mexico, on an assignment

for the Boeing Company, it was brought there with

our household effects in a moving van. Then, when Boeing

reassigned me back to Seattle, it was flown back to Seattle

along with our other belongings. This came about because

the airplane used to bring the guided missiles down to

New Mexico for test firings were otherwise empty when returning.

It is a well-traveled keepsake. Off in one corner, there were

two framed oil portraits. These portraits depicted

Off in one corner, there were

two framed oil portraits. These portraits depicted

In 1882 Hans C. emigrated from what was then Germany

but had been Denmark before 1868. (His home town of

Sonderburg was finally returned to Denmark in 1920, as

part of the settlement after World War I.) Times

were hard, the Germans treating the Danes as

second class citizens in that part of Denmark. He

didn’t like his children being forced to learn

and speak only German in school.

In 1882 Hans C. emigrated from what was then Germany

but had been Denmark before 1868. (His home town of

Sonderburg was finally returned to Denmark in 1920, as

part of the settlement after World War I.) Times

were hard, the Germans treating the Danes as

second class citizens in that part of Denmark. He

didn’t like his children being forced to learn

and speak only German in school.

My Uncle Frank donated them to a

museum newly established in Brayton in the

mid-fifties when he left Brayton, to move to Seattle. Whether

they are still there, or if they may have been moved

to Elk Horn I don’t know. Most of the tools were made

of wood, with steel blades inset. There were augers of

different sizes for boring holes up to about two inches in

diameter. Each had its own permanently fastened handle.

There was also a brace and bit for smaller holes, the

brace itself of wood, and the steel bit was flat with sharpened

angles on its two opposite edges. There were several

wooden planes, very well made. Records found by Frederick

show that Hans C’s father came to Sonderburg from the

Baltic island of Bornholm, and that he was also a ship’s

carpenter. Might some of those tools have been his father’s?

I have inherited some of the tools my father used

as a shipwright and a carpenter, so why not?

My Uncle Frank donated them to a

museum newly established in Brayton in the

mid-fifties when he left Brayton, to move to Seattle. Whether

they are still there, or if they may have been moved

to Elk Horn I don’t know. Most of the tools were made

of wood, with steel blades inset. There were augers of

different sizes for boring holes up to about two inches in

diameter. Each had its own permanently fastened handle.

There was also a brace and bit for smaller holes, the

brace itself of wood, and the steel bit was flat with sharpened

angles on its two opposite edges. There were several

wooden planes, very well made. Records found by Frederick

show that Hans C’s father came to Sonderburg from the

Baltic island of Bornholm, and that he was also a ship’s

carpenter. Might some of those tools have been his father’s?

I have inherited some of the tools my father used

as a shipwright and a carpenter, so why not?  good drawings of horses. My dad

said his grandfather did those for his own amusement when

the walls were newly plastered. Dad had been required to help with

mixing the plaster and carrying it up to the man

who had been hired to do the actual plastering. He said

the plasterer kept calling, “More Mud!” before he could

get the next batch mixed. I recall feeling sad when the

new wallpaper went up and I could no longer see those fascinating

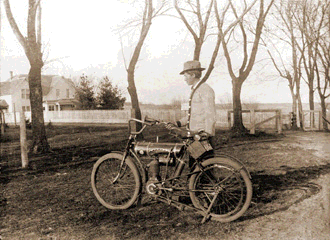

drawings. The house he

built was remodeled more than once. The picture to the right,

depicts great grandpa Albert (Hans C's grandson), in 1910, standing with

his motorcycle in front of the house that Hans C. built.

good drawings of horses. My dad

said his grandfather did those for his own amusement when

the walls were newly plastered. Dad had been required to help with

mixing the plaster and carrying it up to the man

who had been hired to do the actual plastering. He said

the plasterer kept calling, “More Mud!” before he could

get the next batch mixed. I recall feeling sad when the

new wallpaper went up and I could no longer see those fascinating

drawings. The house he

built was remodeled more than once. The picture to the right,

depicts great grandpa Albert (Hans C's grandson), in 1910, standing with

his motorcycle in front of the house that Hans C. built.